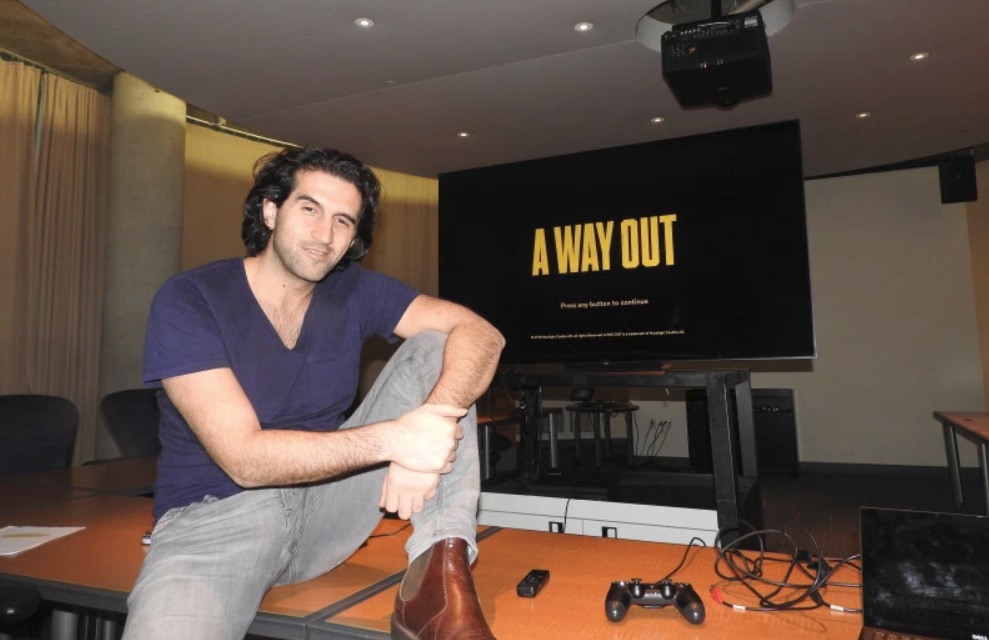

Josef Fares made gamers laugh during The Game Awards when he yelled “f*** the Oscars” into the camera, saying that games are where it’s at. And the writer and director at the Hazelight game studio promised that “you can break my legs” if you don’t like his new game, A Way Out, when it comes on the consoles and the PC on March 23.

The game is a risky venture, and it will be published by Electronic Arts as part of its EA Originals label. It is a two-player co-op only game, where you play as the brash Leo or the calm Vincent as the two try to escape from prison and reunite with their loved ones. The action takes place on a split-screen TV, but the human players control one character or the other simultaneously.

Unlock premium content and VIP community perks with GB M A X!

Join now to enjoy our free and premium membership perks.

![]()

![]()