Editor's Note: I really see where Cameron is coming from here. If we — the people who write about games — are not willing to tackle issues beyond frame rates and review scores, we have nobody to blame but ourselves for the demonization of the gaming industry by news outlets. This may be easier for me to say since I'm still mostly an outsider to the industry, but I've never understood why so many people who write about games seem to be afraid of truly being critical of their medium. – Jay

Let me start with a little confession: about three years ago, I got so sick of listening to game journalists and consumers of game journalism navel gaze about the review process that I stopped listening to these conversations. When this topic comes up on a podcast, I skip forward until the discussion is over. When people write about it, I generally don't read it. I lost interest in the debate a long time ago. However, that's not because the subject isn't interesting. It's because the way people discuss it is unlikely to affect on the way we talk about games in any interesting way. To put it simply, I think everyone is missing the point.

Let me start with a little confession: about three years ago, I got so sick of listening to game journalists and consumers of game journalism navel gaze about the review process that I stopped listening to these conversations. When this topic comes up on a podcast, I skip forward until the discussion is over. When people write about it, I generally don't read it. I lost interest in the debate a long time ago. However, that's not because the subject isn't interesting. It's because the way people discuss it is unlikely to affect on the way we talk about games in any interesting way. To put it simply, I think everyone is missing the point.

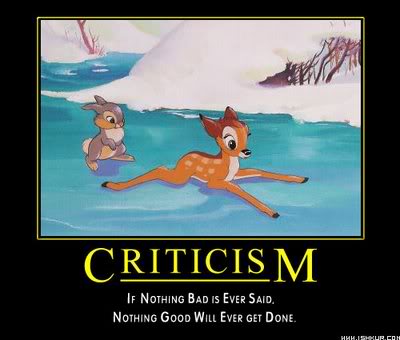

So why chime in now? Something related to this seemingly endless discussion has really started to rub me the wrong way. Namely, I'm tired of hearing people who get paid to write about games for a living — who are in a position to make the changes that everyone kvetches about — resolutely refuse to call themselves critics, instead taking solace under the banner of “reviewers.” I'm sure that people use that word for different reasons, and that some probably do it for no reason at all. But whether they use the word innocently or as a way to dodge the responsibility that comes with calling themselves critics, “reviewer” may well be the most pernicious word in game writing today.

I had already been thinking about this when some music and film critics started reacting to a Boston Globe piece by former music critic Steve Almond, in which he writes off music criticism as “a pointless exercise.” His reasons for that pronouncement struck me as germane to the way a lot of gamers and “reviewers” think of game criticism:

“The very idea of music criticism — of applying some objective standard to the experience of listening to music — suddenly struck me as petty and irrelevant. I spent several more months as a critic, but my essential belief in the pursuit evaporated.”

I don't know how many people who write game reviews share Almond's assessment of the goal of criticism, but I've long suspected that most do. It would explain why so many game reviews follow the exact same formula of reporting on whether the game at hand lives up to current technical standards of graphics, controls, and basic functionality. Then they toss in a couple of words about whether the plot makes sense and state whether or not “fans of the genre” will enjoy it. That formula seems tailor-made to minimize the subjective input of the critic, though it has the unfortunate side effect of making sure reviews have as much chance of challenging the reader's thinking as a Consumer Reports article.

The rejection of the value of criticism is part of a larger anti-intellectual streak in contemporary western culture. The easy availability of information has convinced us that we're all our own experts, and that has lead to a great many people taking grave offense when actual experts state their opinions. When I see people in the field of game writing who could legitimately be called experts rejecting the mantle of "critic" in favor of "reviewer," I get the impression that it's in response to this anti-intellectual outrage. “Critic” has too much intellectual baggage. Calling yourself a critic just asks for angry comment threads, hate mail, and accusations of being overweight. A lowly reviewer has far less responsibility.

Of course, I have no way of knowing what people who call themselves “reviewers” are actually thinking. Really, it doesn't matter because my point isn't to condemn them. I'm making the case that having people willing to self-identify as video game critics would be good for the image of the medium and for the edification of gamers. This is especially true if some of these people take the time to really learn about criticism and how to talk about games in a wider artistic context.

Of course, I have no way of knowing what people who call themselves “reviewers” are actually thinking. Really, it doesn't matter because my point isn't to condemn them. I'm making the case that having people willing to self-identify as video game critics would be good for the image of the medium and for the edification of gamers. This is especially true if some of these people take the time to really learn about criticism and how to talk about games in a wider artistic context.

We can't go on saying “It's just a game” every time someone wants to have a serious conversation about the significance of something like the No Russian level in Modern Warfare 2. If game writers aren't willing to make the case that games have the same social and cultural significance as books, movies, and music, then they don't have the right to complain when cable news pundits set the tone of the discourse and portray games as an entirely negative influence on society. Critics can combat that kind of thinking, but reviewers can't be bothered. They're too busy writing about the really important things, like frame rate and texture pop-in.

Whether or not they're using the word as a way to excuse themselves from serious conversation, reviewers need to grow up and learn how to be critics. They need to stop being afraid of the lowest common denominator — the misanthropes who vent their frustrations in the comment threads of writers whose opinions are too complex to be expressed by a single number between 1 and 10. Those people will always cause trouble, and they will never matter. We shouldn't let them determine the intellectual level of video game writing any more than we should let Twilight fans determine the tone of literary criticism. Not even if they call us fat.