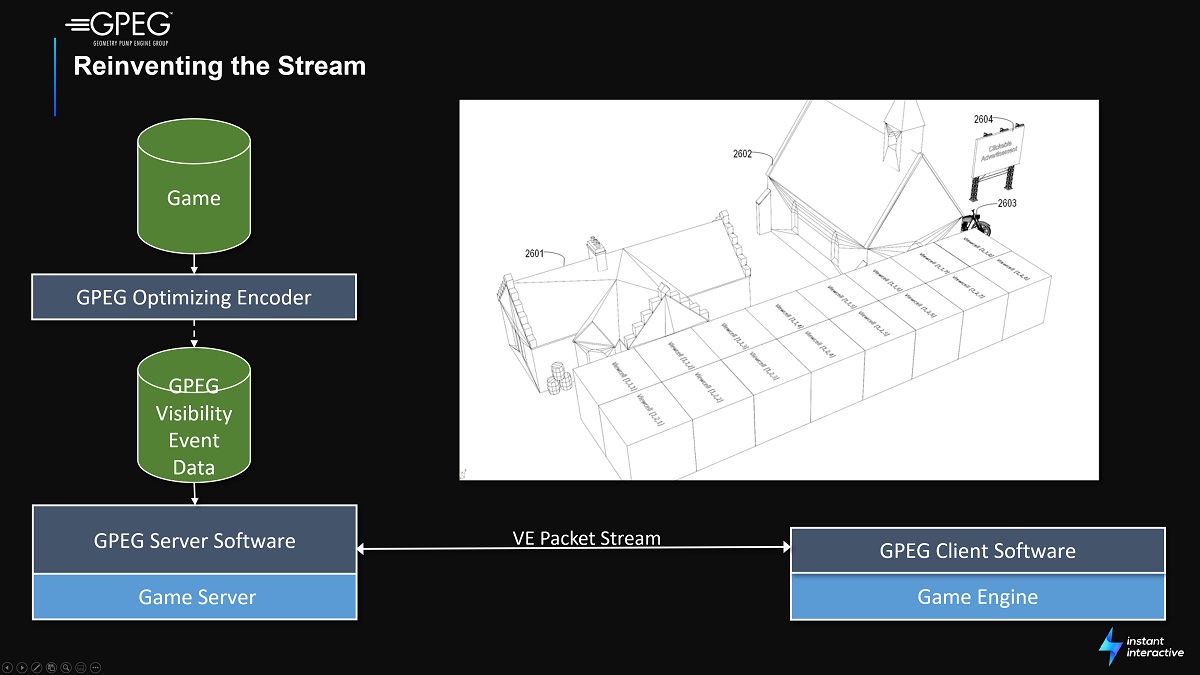

Primal Space Systems has raised $8 million for its subsidiary Instant Interactive, and it’s going to use it to make a technology dubbed GPEG, which is like a cousin of the MPEG format used to run videos, but for graphics.

But GPEG, a content streaming protocol, is a different way of visualizing data, and its creators hope it could be a huge boost for broadening the appeal of games as well as making people feel like they can be part of an animated television show. Instant Interactive wants to use its GPEG technology to more efficiently stream games on the one hand, and on the other, it wants to turn passive video entertainment into something more interactive and engaging.

Unlock premium content and VIP community perks with GB M A X!

Join now to enjoy our free and premium membership perks.

![]()

![]()