Editor’s note: Games can be trivial bits of entertainment, but can games deliver a political message as well? Christopher examines the question. -Jason

The growth of the gaming industry has led some to argue that video games are not just a form of entertainment medium but also a legitimate process to deliver compelling — even political — narratives.

I’m not so concerned about whether video games can deliver such a narrative. Rather, would it be beneficial for the industry to pursue and discuss issues such as social class, gender, and racial inequality? Would the industry gain a wider audience if it delivered a serious debate surrounding crime and punishment?

I do not believe so, nor do I feel that the industry needs to take on such responsibilities.

It’s evident that video games reflect social politics. We’ve been involved with and read articles about the treatment of sex or the portrayal of relationships (and gender) between characters in games, the representation of ethnic groups, the use of violence in gaming, and even games as art.

It seems what these articles advocate is a more “mature” and “serious” approach to these topics in games.

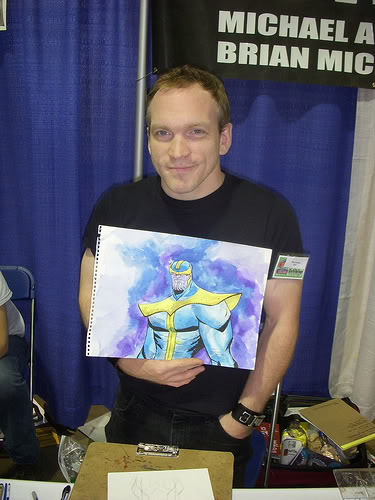

And it’s because the gaming industry has arrived at this particular junction that the video game and the comic industry are drawing closer to each other. This is exemplified by Valve’s recent acquisition of the services of comic-book writer Mike Oeming to work on their cross-media product and Jim Lee’s extensive involvement with DC Universe.

If we examine the road that has already been paved by the comic industry, it’s clear to see why video games may follow a similar path.

In America, the comic book industry helped the nation reconstruct itself from the aftermath of the economic depression in the 1930s.

Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, and Hal Foster’s adaptation of E. R. Burroughs’ Tarzan became a force that helped shook away the gloom of the Depression.

Comic books not only provided a need form of escapism for American youth in the ’30s and the ’40s — they also provided inspiration. This period’s now known as The Golden Age in the comic industry and blossomed three essential genres in the arena of legitimate narratives: science fiction, detective stories, and jungle adventures.

Even to this day, these three genres influence our culture. Star Wars would have never been conceived if a young George Lucas hadn’t been exposed to the adventures of Flash Gordon.

Gould’s Dick Tracey took Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and repackaged it into a slick, easily digestible experience for the new century.

Comics today are vastly different to the comics of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s.

Superman no longer sells the numbers it did in the ’50s. In fact, Superman’s wholesome image that made him a role model of the ’50s has now become his greatest setback. We don’t want perfect heroes. We want Alex Mercer, Wolverine and The Dark Knight (not the Caped Crusader version of Batman.)

The Voice of Gaming

Video games will have the same affect on the movie industry as comics had on the print industry. It will provide an alternative approach to experience a visual, motion picture-esque narrative.

But do video games need legitimately tough narratives to ensure their voices are heard? No.

I don’t think actual in-game experiences need to tackle poverty or racial inequality head-on to change the current state of affairs that we live in.

Sometimes subtle satire and indirect references can resonate a stronger truth than direct honesty itself.

Would SimCity be any better if it allowed you, as the mayor in the game, the power to oust all the Jews? Or incarcerate all Muslims for fear of terrorism? By giving the power to do such sensational actions, would the game appropriately cover or teach a message of cultural intolerance?

Would games such as historically-based first-person shooters benefit from showing us the atrocities of war as the media had done in the ’60s with the conflict in Vietnam? Should we invite the true horrors of war into our home?

In Civilization, would showing the full impact of poverty and famine striking my Civ-nation make the player give money to charity groups such as Red Cross?

Then there’s always the fear that the game itself will promote the developer’s or publisher’s own political and social interests. I remember reading somewhere on the cover of my Assassin’s Creed game a small disclaimer that read something like: This game was built by groups of people from all religious beliefs and social backgrounds.

In no way did I interpret the game as slanderous toward the two factions (Christians and Muslims) portrayed because I understood the product to be a game, not a political statement or propagandist process.

Then there was Resident Evil 5 and the recent dropping of Six Days in Fallujah. Japanese developers have had enough criticism regarding insensitivity toward cultures.

Ultimately, games will never be able to carry a political message because it’s more about a game having high market saturation as opposed to the spiritual or humanitarian in-game message.

Unlike comics, where the audiences are still a select group within society, games have the ability to penetrate the mainstream market in a way that comics have yet to achieve.

Video games are the hybrid of the movie industry and the comic industry. They have the mainstream appeal of movies but can exercise the political and visual language found in comics. It is because of this that video games will always be chastised when it comes to commenting on sensitive social political issues.

Too much is at stake beyond the message. The money, the media representation and the general shadow of “triviality” will always trail the word “game,” because that is what makes it open to all markets. Video games will always be associated with the words such as pastime, relaxation, fun, children, fictitious (the list would go on), and that’s why game will never have a serious political voice.

Unfortunately, some tags can never be thrown away. Hitler will always be a bastard, Matt Damon will always be a bad actor — no matter how many politically serious or heart-wrenching films he tries to do — and video games may never carry the weight to cover social or political issues.

Unfortunately, some tags can never be thrown away. Hitler will always be a bastard, Matt Damon will always be a bad actor — no matter how many politically serious or heart-wrenching films he tries to do — and video games may never carry the weight to cover social or political issues.

But is that a bad thing?