Game theory strives to answer some illusive and nebulous questions, or at least suggest possible explanations. What makes a game compelling? What makes a game frustrating? What about a game engages, motivates, excites, stimulates, and entices players? Venturing a theoretical answer requires diagnosis. This is a difficult undertaking with any art form.

Game design is not a science. However, there is a more recent branch of game theory called “game feel,” which asserts the supposition that graphics, sound, feedback, and controls coalesce to produce a distinct feeling. It’s similar to traveling. Different places have their own indelible, experiential, and personal residue they leave on you, and the mere process of remembering a place elicits a distinct “feeling” that you associate with it.

Game designer Steve Swink calls game feel "the tactile sensation of manipulating a digital agent. The thing that makes your mom lean in her chair as she plays Rad Racer. Proxied embodiment." It is that intangible magic that gives pixels their context and gravity and galvanizes the player. It has the capacity to displace you, transplant you into the soil of the game world, and if you acclimate, you’ll find a place with weight, weightlessness, object permanence, object impermanence, and all of the worldly and otherworldly fibers that transmit impulses across the fabric of a game.

Good game feel is illusory, yet convincing and absorbing. The game acts upon us with a proposition, we provide a kinesthetic reaction, the game converts that physical input into its own language and then offers a sympathetic response. This volley of action and reaction between player and program must be fluid, balanced, and supplemented with the appropriate graphics and sound to establish strong game feel. Swink further breaks down game feel like so:

- Input — How the player can express their intent to the system.

- Response — How the system processes, modifies, and responds to player input in real time.

- Context — How constraints give spatial meaning to motion.

- Polish — The interactive impression of physicality created by the harmony of animation, sounds, and effects with input-driven motion.

- Metaphor –The ingredient that lends emotional meaning to motion and provides familiarity to mitigate learning frustration.

- Rules — Application and tweaking of arbitrary variables that give additional challenge and higher-level meaning to motion and control.

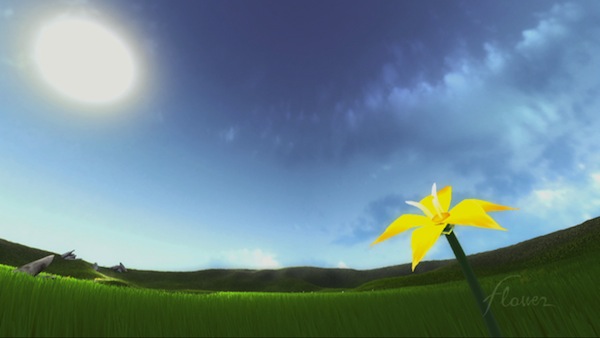

When considering game feel, I believe an important work to examine is thatgamecompany’s PlayStation 3 title Flower, because of how it relies on game feel while also complicating the issue of fun. It possesses a strong native voice, sense of place, and an argument that relies on gameplay, not dialogue.

Flower is a rare breed. Most games have created game feel in service of "fun," without any interest in venturing into the vast spectrum of untapped of human emotion. Such games primarily introduce crude and trivial alterations to their feel throughout the movement of the game. Flower captures, on a smaller scale, what film does so well: It presents a broad potentiality of emotional range through action, image, metaphor, and sound, which undergo discrete movements and transformations throughout seperate acts.

It is no accident that Flower is so interested in tilling a rich aesthetic and intellectual experience. Game feel appears to have been a central concern in the game’s development since its conception, when it was just an emotional reaction to a new environment. Lead designer Jenova Chen describes the earliest germination of Flower:

Flower is mainly inspired by my trip from China to the US. I grew up in Shanghai, a concrete metropolitan. In the entire 24 years, I rarely left the city. And when I came to California and saw the endless grass field and the windmill farms on the rolling hill next to the freeway, I was completely shocked by the view. The sense of being engulfed by nature is something sublime that I can't capture with photos or videos. As a game designer, I wanted to try to capture that feeling with an interactive experience, and that is how I started the concept of Flower.

Chen began Flower as a feeling, not as a mechanic. It is a work that was created as an attempt to capture that feeling of awe Chen experienced, when environmental degradation gave way to the prosperity and intrinsic beauty of biota. It seems that many developers begin projects by starting on a foundation of rules, story, and genre, rather than feeling, emotion, and theme.

Flower is certainly an idiosyncratic and abstract title, but it's one that has managed to garner mainstream interest and positive critical reception. It has won numerous awards, including the BAFTA Video Game Awards’ Artistic Achievement award, and IGN’s PS3 Special Achievement for Innovation award. I believe that Flower’s success and artistic strengths rest in its keen attention to game feel.

Much like Godfrey Reggio's 1982 documentary film Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance, Flower begins in regions of rural isolation and moves into the cul-de-sac of human urbanization. The game’s first and second levels, which Chen refers to as dreams, are set in a meadow devoid of any human artifacts. The third dream introduces wind turbines, which it depicts as constructive technological application by preserving the positive game feel and tone of the preceding levels. The fourth dream introduces power lines and agrarian machinery, but positive game feel is maintained in this level. In the fifth level, the flower’s journey goes from a tranquil dream to a nightmare.

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VjIR69Aj92Q&feature=related ]The wasteland of Dream 5.

You enter a desaturated, devastated landscape that has been ravaged by an electrical fire. The ruins of power plants, pipelines, and wires are strewn throughout the environment, holding a new purpose as obstacles. The ambient sounds of nature recedes and the vibrancy of old growth dims to a uniform grey. Certain flowers are tucked away in the skeletons of electrified girders, and touching any part of these towers destroys all of the petals you’ve amassed, sparing only your lead petal. When this occurs, a shocking pulse of vibration rattles the controller, the screen blackens, and a hissing sizzle of electricity is produced.

All of these elements come together to change the game’s feel. The nightmare encourages new feelings of trepidation, anxiety, and loss. It does so by adding punitive rules and regressing color diversity, visual effects, jarring feedback, and sound. The game suggests that man-made machines that instigate environmental degradation prompt these feelings, a metaphorical relationship between game feel and artistic statement.

The final dream, however, takes the player into a city that initially resembles the fifth dream. It is desaturated, lacking biota, and congested with monolithic spires of steel and rubble.

But as the player triggers context-sensitive flowers, color, sound, and biota are added to the environment. Colliding with industrial monoliths destroys them, and they dissolve away to grant access to new sections. In a sense, the player is restoring life and prior game feel to the level. The soundtrack becomes more triumphant and cheerful as the player paints the city with color and plant growth, sewing interactive opportunities into its impoverished soil.

Though it was not mandatory for level completion, I found myself seeking out every last dormant flower in order to restore the whole environment. I could not bear the thought of leaving the city with a single patch of grey remaining. By giving the player the ability to restore the game’s feeling to its most stimulating and interactive roots, environmental degradation gives way to environmental reclamation, and summarizes the dialectic between the two.

Flower’s game feel strengths (using the Swink model):

- Input — Simple and intuitive controls acclimate player to game space quickly and place attention on engaging with the environment.

- Response — Motion is predominantly fluid and changes with triggered alterations to wind and space.

- Context — Open fairways of flowers and varied topography do not constrict the player, but instead empower them to navigate freely.

- Polish — Lush, detailed landscapes are gardens for satisfying response systems that greet collision with dynamic aesthetic transformation and sound emission.

- Metaphor — Man-made environmental degradation strips away previous gameplay opportunities, but are later reinstated by the player through environmental reclamation.

- Rules – The absence of losing conditions allow for uninterrupted exploration. However, special case constraints in the latter portions of the game may make players rethink unobstructed, harmonious flight.

Flower shares a mechanical history with many games, such as Snake, various flight games, and its developmental ancestor, flOw. Yet it is quite distinct, due largely to its feel.

How does it feel? I can say that while I was playing it felt lyrical, meditative, harrowing, serene, peaceful, violent, calming, stressful, empowering, ethereal, frustrating, delicate, and rewarding. But these are just adjectives and poor substitutes for the act of feeling. Did it feel fun? Only in the moments when I was reminded of a similar childhood experience, a time when the concept of fun was better known to me.

I hesitate to call Flower’s feel — or any game's feel for that matter — fun. It seems to me too broad of a word, and at the same time, too narrow. Qualitatively, it says nothing. It denies the entire emotional spectrum of human beings, and this is problematic when considering that game feel to many falls under the branch of “theories of fun,” and the word fun is so commonly used in gaming discourse by developers, theorists, journalists, and consumers alike. Fun nearly even swayed the vision of Flower:

At one point in its production, Flower included mechanics like spells — after Sony said the game needed more depth — yet play testers were only shouting out expletives or cheering when they succeeded. These base emotions weren't what the team were trying to convey, so despite purportedly "making the game more fun," Chen had the features cut out.

The 10-year-old me would say many parts of Flower were not fun. Some sections even seemed antithetical to the prosaic, commonly held ideal of “good” game feel: design in service of fun, whatever that is. Is fun competition? Is it completing an explicit goal as efficiently as possible? I believe game feel to be a sound theory for what gives games their character and ability to affect the player in impactful and absorbing ways. But it seems to me that there are a majority of players that have a homogenized view of game feel (especially those that have experienced game feel, but do not know it by its clinical definitions).

Some players refer to game feel offhand by saying things like the controls are “tight,” the game looks “gorgeous,” or it feels “unresponsive.” What about games with clunky controls, an ugly aesthetic, or unresponsive feedback that make those choices deliberately to advance a desired tone, emotional direction, and ultimately, game feel?

Some might say that those elements would still be capital offenses to good game feel, which should always encourage, reward, and pacify the player, as in the positive reinforcement model of Peggle. Perfect game feel then becomes a neverending cavalcade of encounters, gambling with a shotgun, a blunt instrument, excitement on-demand, a prescient software genie that continuously appeases the customer, who is always right.

It's of vital importance that games find their own native voice and formal conventions. What games can learn is how to create a movement, a season of vagaries, arbors of transition, stillness, emotional and thematic diversity, driven purely by form and aesthetic, and not dialogue, character, or non-interactive scenes.