Professional wrestling has its origins in late-19th- and early-20th-century American carnivals, where it initially resembled mixed martial arts more than a testosterone-fueled soap opera. Carnivals would pit skilled fighters against locals from the audience in very real, unscripted fights. These bouts often ended with the hometown heroes receiving a healthy beating for their bravery and idiocy.

It didn't take long for promoters to realize injury rates were high in a real setting, and that it might be better for everyone if they fixed the fights. Wins and losses would be important of course, but outcomes would be predetermined so that the touring wrestlers would look strong, intimidating, and obnoxious, leading to the inevitable moment when the hometown boy (now a planted actor in the audience) would triumph.

To hide the clandestine nature of the deception, wrestlers would couch their language in carny speak. The trick was to get the audience to believe in the "work." The evil touring fighters were heels against the local town babyfaces. Audiences who bought into the show, and they were huge in number, were all marks.

Finally, and most importantly for the purposes of this piece, it was thought that if audiences stopped believing the fights were real, they'd stop buying tickets, so it became necessary for wrestlers to protect the business, or maintain "kayfabe" at all costs.

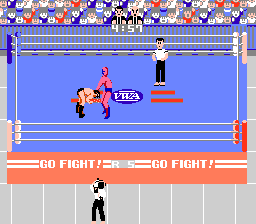

Pro Wrestling appeared on Famicom disc systems in 1986 and the NES in 1987. It is a game where, playing characters largely based on popular Japanese wrestlers of the era, you pummel your opponent in the hopes of becoming the champion.

While it's true that upon Pro Wrestling's release, promoters were still protecting kayfabe to an extent, it was clearly dying a slow death — the comic book antics of Vince McMahon's WWF (now WWE) superstars weren't helping. To get around state athletic commission laws, McMahon declared in the '80s that pro wrestling was not a sport, but "sports entertainment." As the Internet took hold, fans quickly clued in, at least to an extent, to what was going on. WWE fans no longer believed that their sport of choice was a sport at all, but a dangerous, high impact stage show.

WWE Smackdown Versus Raw 2011 goes on sale in October 2010. It's a game where, playing characters licensed from McMahon's empire, you pummel your opponent in the hopes of becoming the champion. Huh?

Kayfabe is very much still alive in wrestling video games, and this is what often disappoints me about them. I wrestle sporadically, training and performing in front of audiences as a weekend hobby, rather than an occupation. I know that the joy of professional wrestling is not in the thrill of competition, but in telling a story to an audience in real time. Rather than following detailed scripts, those at the very top of their game can read an audience, tell what they want to see and adapt their game plan on the fly. In tandem with their opponent, they cab create an emotional roller coaster.

Yet, THQ's offering — along with Konami's imminent AAA: Heroes Del Ring — does not appeal to this sensibility at all, feeling more like a beat-em-up. At Microsoft's pre-Tokyo Game Show keynote, meanwhile, Spike unveiled an XBLA avatar based on a follow-up to its long running Fire Pro Wrestling series. This news piqued many people's interest because the Fire Pro franchise has been one of the few to get things right.

While most games in the series have taken the same format as every other title — beat guys, then win — the impressively in-depth Fire Pro A and its follow-up Fire Pro Final on Game Boy Advance wouldn't determine the outcome of a match on the basis of a knockout but rather, on the audience's reaction to the match. The game calculated the excitement level by how balanced your match was and whether you adhered to your chosen wrestler's style — adopting the Japanese King's Road fashion or performing dangerous flip-dives onto opponents in Mexican Lucha Libre style earned you extra points.

While most games in the series have taken the same format as every other title — beat guys, then win — the impressively in-depth Fire Pro A and its follow-up Fire Pro Final on Game Boy Advance wouldn't determine the outcome of a match on the basis of a knockout but rather, on the audience's reaction to the match. The game calculated the excitement level by how balanced your match was and whether you adhered to your chosen wrestler's style — adopting the Japanese King's Road fashion or performing dangerous flip-dives onto opponents in Mexican Lucha Libre style earned you extra points.

Fire Pro FInal took things further with a Management of Ring mode that put you in charge of your own promotion, booking the type of matches fans would want to see. 2004's King of Colosseum 2 on the PS2 would take this approach even further, with more complex ranking algorithms for your gameplay and licensed grapplers. It's unlikely that the new Fire Pro, shunning gritty 2D sprite art for cartoony avatars, will follow suit, which is a shame.

American-produced wrestling games occasionally give a nod to the goal of winning an audience's money, but Acclaim's dreadful Legends of Wrestling series had an audience satisfaction meter that took things to a horrifying new level. Players filled the meter by simply grinding a checklist of objectives that were the same each match. Even worse were the General Manager modes in previous Smackdown games, which gave matches ratings based purely on the popularity of characters involved, rather than the actual performances.

You could make the argument that, by admitting the deception behind pro wrestling, modern video games would politicize the genre and make things too complex for casual fans to enjoy. A happy medium exists, however:

One of the joys of Fire Pro is the number of things going on behind the HUD-less scenes. Early in a match, opponents are more likely to counter big moves, forcing players to start small and build up. Fire Pro encourages players to take risks with their wrestler's repertoire and whip the fans into a frenzy. Players on the receiving end of a beating, however, find that the game's invisible momentum bar works in their favor. While losing, if a player takes a chance with a big move, they're more likely to score and keep the match alive. It captures some of the essence of a real professional wrestling match, and regardless of how "smart" you are as a fan, it makes things more believable and exciting.

WWE games, meanwhile, seem more about hitting signature moves almost right out of the gate. More than simply having light and heavy grapples available, why not change the player's moveset entirely? Moves could be dependent on the stage of the match and the fans' level of enthusiasm. Why not carry the drama that THQ successfully conveys backstage into the ring?

Ironically, while people direct a lot of criticism at pro wrestling's convoluted storylines, poor booking of matches, and an overemphasis on the entertainment rather than the sport, you could make a case that we should let wrestling games entertain us more.