Editor’s Note: This well-written piece by Omar Yusuf dives into the complexities of conflict in literature and why videogames need to explore them more. And just so I don’t scare you off with that synopsis, he talks about shooting stuff, too. -Shoe

Conflict, in its most narrative sense, is a fundamental element in all fiction. Without a source of struggle or strife, literature and films can appear vacuous or inane. Conflict generates a sense of purpose, a hurdle which must be overcome — whether in the name of peace or triumph.

English classical literature has evolved in such a way that conflict is often categorized into one of several archetypes. These include: “Man vs. Machine,” “Man vs. Nature,” and the like. For the most part, these categories do their part; they make it easy to understand conflict in whatever context, whether it’s between Luke and Darth Vader or between Holden Caulfield and the unkind New York City society.

Conflict in literature, the arts, or motion pictures is rarely physical. Often, it can be psychological or rhetorical, as categorized under “Man vs. Self” or “Man vs. Society.” Christopher Nolan’s Memento observes the strife which erupts when a man fights with his own memory and past. Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies depicts the struggle which a boy and his young sister have to endure with poverty and neglect. Hell, even Aqua Teen Hunger Force has instances where Master Shake fights obtuse and intangible elements such as reputation, self-esteem, and identity.

Why is it then, that the majority of conflict in videogames boil down to shooting at nazis, terrorists, and aliens?

The simple answer? In the context of a videogame, shooting at Nazis is more fun than struggling with depression or heartbreak.

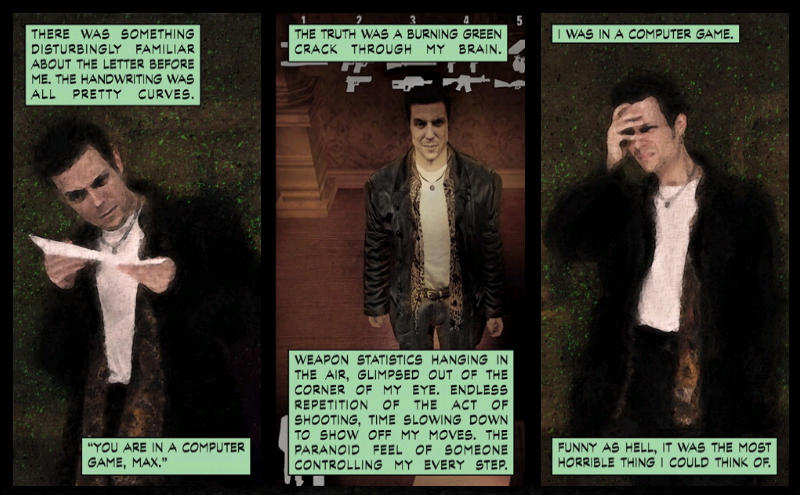

But here is the problem. In videogames, the player almost exclusively interacts with the world via the end of a weapon. Neither plasma rifles nor throwing stars are useful in a conflict which involves ideas, words, or beliefs. Some very story-driven games cross milestones in dealing with non-physical struggles. Max Payne, by the end of the sequel, reconciles with the fact that he is indeed one of the “bad guys” — only after admitting that in the world we all live in, everyone is bad.

Max Payne breaking the fourth wall.

I’m not asking for a game which involves quick-time sequences where you “tap A” to take three tabs of prozak or “rotate the analog stick” to take yet another swig of brandy. I love shooting things, especially Nazis and aliens (and Nazi-aliens). I’m simply asking for a little more sophistication in the narrative of videogames.

A good many of the articles on Bitmob deal with symptomatic issues which prevent the videogame industry from being considered a viable expressive medium. Art has the capacity to communicate complex issues. I think we’ll all agree that pointing an M1 Garand at a Nazi’s head is far from “complex.”

Games like Call of Duty and Medal of Honor have the capacity to convey a more genuine look at the Second World War. Not all the German soldiers had affiliations to the Nazi Party, and in fact, many Wehrmacht members were Polish or Dutch conscripts. WW2 franchises have the opportunity to display the brutality and senselessness of war, instead of the perceived glory. Nazis are bad. No doubt about it. But things are more complicated than that, and I encourage games to delve into that complexity and expose it.

Perhaps Call of Duty 2 could have portrayed all the members of both opposing factions as being “evil,” simply by virtue of taking the lives of one another. It could have just as easily gone the other way, by interpreting all soldiers as innocent casualties to wars which they would never fully understand.

But that doesn’t sell. Everyone wants to shoot aliens, nazis, and terrorists. No questions asked.

Half-Life is a game which possesses enthralling weapon mechanics, graphics, and sound production. But the reason it’s an important game is because it deals with narrative elements such as inevitability and human futility in a way which is interesting and more vivid.

The “bad guys” in videogames need to emulate (or at least reflect) the “bad guys” in real life, especially if videogames want a bid at being taken seriously. Most things in life have some element of evil associated with them, but the writers and producers of videogames would much rather deal with things that are viewed as being “absolutely evil,” such as gun-crazed terrorists or hostile aliens.

The world rarely operates in absolutes. The world is more ambiguous than that. I think it’s the job of videogames to highlight that ambiguity…and let us shoot it in the face!