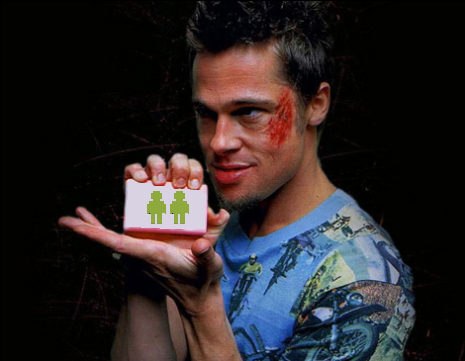

Two years ago, my doctor diagnosed me with acute, chronic insomnia. While the term has become synonymous with mild sleeplessness, it's always been far more intense in my case. Imagine Edward Norton in Fight Club, then dial it down one or two steps. At times, an uncontrollable alertness grips me for days and sleep is impossible. Regardless of my mental or physical fatigue, my body will refuse to fall unconscious. While insomnia doesn't create pain, necessarily, it's indescribably uncomfortable.

Two years ago, my doctor diagnosed me with acute, chronic insomnia. While the term has become synonymous with mild sleeplessness, it's always been far more intense in my case. Imagine Edward Norton in Fight Club, then dial it down one or two steps. At times, an uncontrollable alertness grips me for days and sleep is impossible. Regardless of my mental or physical fatigue, my body will refuse to fall unconscious. While insomnia doesn't create pain, necessarily, it's indescribably uncomfortable.

For approximately four months, I relied on heavy sedatives to get to sleep: Quazepam, Midozolam, Triazolam — you name it, I tried it. Sleeping pills certainly knocked me out, but I'd never get a solid night's rest. Last November, I started taking a new form of medication: video games.

I've found that the best remedy for insomnia is 30 minutes of gaming. I don't mean to claim that video games bore me to sleep — in fact, it's the opposite. An intense round of Left 4 Dead's Survival mode will suck out any excess liveliness I have and leave me practically comatose.

Video games have had an immeasurably curative effect in my life. Justifiably, my experiences have left me curious about the implications of games as a form of healthcare. While insomnia is nothing to scoff at, the disorder pales in comparison to the severity of paralysis or cancer. The question is whether video games represent a feasible form of treatment. The answer? Sort of.

After a car accident dealt nine-year-old Ethan Myers a severe brain injury in 2002, his doctors pronounced him brain dead. When the boy woke from his month-long coma, the doctors maintained their grim forecasting by claiming he would never walk or speak again.

Today, Ethan has caught up in his academics, restored his motor functions, and has even delivered a speech to an audience of his peers. These developments can be attributed to, in part, video games. For several months, Ethan played enhanced games that used a neurofeedback program called CyberLearning. The system rewards players for producing particular brain waves, especially those which appear when a person is at ease or concentrating.

However inspiring, Ethan's story isn't unique. Hospitals around the world are integrating video games into their psycho and physiotherapeutic programs. Below is an photo of James Mann, a 70-year-old patient at Wake Medical. He is a recovering stroke victim, and the Nintendo Wii has helped him regain balance, coordination, and strength in his upper body.

While games possess several intangible qualities like artistic and entertainment value, they offer several practical benefits. Without sounding too melodramatic, it's clear that video games are changing and saving lives each day.

Most of you may not be aware, but approximately one-third of US veterans of the Iraq War return home with complex psychological disorders. The most commonly recorded problem is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Many solders diagnosed with PTSD fail to successfully reintegrate into civilian life due to the battery of traumatic events and sights they were exposed to abroad. But the unlikeliest heroes have saved many of these soldiers: video game developers.

The US military contracted graphic designers and engineers to construct "Virtual Iraq," a 3-dimensional simulator which recreates many of Iraq's sights, sounds, and smells. Below New Yorker writer Sue Halpern narrates a walkthrough as part of her coverage of the therapeutic endeavor for the magazine.

I'll admit the game doesn't look very realistic, but apparently it's helped dozens of soldiers recover from their trauma and eventually reestablish their old lives.

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6kl2BuhKmM ]

Most of us have used video games as a form of self-medication in the past. Pissed off? Play some Unreal Tournament 3 and blast away your troubles. Feeling down? Play a Japanese RPG for six hours and forget about your failing grades or crumbling relationship. The point is that most of you can probably appreciate the therapeutic power of video games. Luckily, scientists and game developers are beginning to do the same, and they aim to ease phobias, calm anxiety, and suppress irrational fears.

Stephane Bouchard, a researcher at the Cyberpsychology Laboratory at the University of Quebec, uses video games to confront and treat phobias. Traditionally, the only cure to a severe phobia has been through a head-on encounter. For instance, if a patient is scared of flying, his therapist will buy a ticket and board the plane with him.

Dr. Bouchard has taken that principle and combined it with new technologies. Bouchard's method involves an Air Canada flight seat and a pair of virtual reality goggles. After being seated, the patient equips the visor and allows the doctor to completely control the experience, by determining factors like speed, altitude, and turbulence. Bouchard's results prove that his method's success rate is impressively high, and due to the falling price of VR equipment, it's surprisingly affordable.

So, can video games really cure all our problems? For now, the answer is "no," but the future seems bright. While video game therapy remains in an embryonic stage, most developers will focus on entertaining their costumers rather than curing them. But I have high hopes for the remedial future of video games. Who knows, maybe in a few years we'll be shooting our cancer cells with Battle Rifles.

Anything is possible!