Editor's note: Educators, take note: Turns out that portable system little Johnny hides under his desk may actually provide valuable insights on how to teach students. Jeremy details how Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker could make you a better teacher. -Brett

Discussions of modern game design require developers to become more aware of their inner teacher, taking into account how players learn as they progress through a game. So it’s no surprise that many recent design sensibilities make use of concepts similar to those found in recent education reform movements. Making tutorials more organic is comparable to creating assessments that test students’ abilities in more practical situations than paper tests.

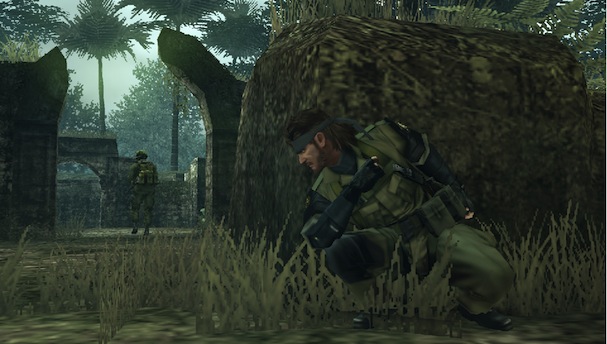

Unfortunately, we never see the flow of inspiration in the other direction. But if we look closely enough, games like Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker can model ways to improve curriculum and assessment.

Making the connection between education reform and Peace Walker requires a little imagination. The usual Metal Gear premise of sneaking around the levels to complete objectives is still in play. However, the structure of the game compartmentalizes the objectives into individual missions. Players can use any method to get through the levels as long as it works, whether they use a stealthy, non-lethal approach or a more action-oriented one. At the end of each mission, the game assigns a grade based on a number of determinants, such as number of times spotted.

Though these grades do try to push players to be stealthy, stealth is not required to finish the game. And if you do go the stealthy route, there are many different options available. Close-quarters combat allows for both quick takedowns and interrogations, while the stun rod tends to be more discrete. The tranquilizer gun works well at a distance and has a limited silencer, but the sniper rifle variety can shoot at a longer range. And that’s not even taking into account the research and development mechanic that forces you to make choices on what tools will be available. In short, the game encourages players to explore its systems in order to develop their own individual approach.

This same principle has been explored in educational psychology theory. Known as individual constructivism, it focuses on how people construct their knowledge as opposed to what the end result is. People take previous knowledge, outside stimuli, and relevant data surrounding the current problem and form their own methods for solving it.

The traditional way of teaching students how to add two-digit numbers together is to line them up and add the columns from right to left, carrying any tens digit results over to the next column. However, not everyone ends up doing it this way later in life. Some use methods that start from the left while others utilize estimation. Many teachers only teach the first method as the only “correct” one when, in fact, there are many different ways to come to the correct answer. And while the correct answer is important, the way which individual students find the answer is where you can truly see if a student has fully understood a concept. If a student can give a mathematically sound explanation of his or her method, then it is valid.

But Peace Walker goes beyond merely mirroring constructivism. The very fact that it is a game gives it an innate advantage over current assessment methods. Paper tests have been the default assessment for well over a decade in classrooms. However, many criticize this method for not properly providing insight into how students apply knowledge to practical situations.

Games, on the other hand, are intrinsically active affairs. Imagine if you had to take a test on effective strategies for fighting a boss instead of fighting the boss itself. When you think in terms of games, this is a ridiculous notion. You’re supposed to take action in games, not describe what you learned up until that point. Bosses are a culmination of your developed skills and knowledge from what came before, much like every programmed instance in a game. You prove your skills have progressed by using them. Imagine if schools did this in place of paper tests.

In fact, this is another educational theory concept, known as performance-based assessment. While many champion this approach, paper tests have become so entrenched in the system that it's had a hard time gaining traction. But all one has to do is point at how games achieve this. The game teaches you how to play in the beginning, builds more complex systems on top of the previous ones as you progress, and provides progressively harder challenges to test your abilities. Looked at this way, games are both curriculum and assessment in one neat package.

Peace Walker is not purely an exercise in systems mastery, either. There is a wealth of ancillary materials in the game for players to view if they so choose. In addition to the optional missions, there are a number of audio files which both provide hints for completing objectives and flesh out the background of the characters and story.

This last part is key, as the story takes place within the real world’s history, albeit with a few fictional additions. Most strikingly, while the Metal Gear games have always drawn from major historical touchstones, Peace Walker taps a relatively underrepresented segment of world history: Central America.

The game takes place in both Costa Rica and Nicaragua, with illuminating background information to match. One can learn about how Costa Rica abolished its army, of the long struggle in Nicaragua between revolutionary Augusto Sandino and the U.S.-backed Somoza family, and a detailed history of Che Guevara.

All of these files are optional, but they can create valuable learning opportunities, which are enriched by the game itself. Creating a learning environment beyond lectures and homework means providing optional materials that students can delve into depending on their interests. The fact that this game can utilize this method to teach players some oft-neglected history is proof that it works.

Before we get too reductive with this analysis, we must realize the reality of our current educational system. Funding is a major problem for many schools, and providing performance-based assessments tends to be expensive. And as much as reformers espouse more organic testing, the truth is that no one approach will magically fix things. It’s going to take smart analysis of individual classrooms and students to see what will work for what situation.

But games at large, including Peace Walker, provide insight into how game design can improve teaching methodology and curriculum building. As unlikely as games seem to be as models for educational reform, teachers would do well to pay attention to how designers teach players.