Editor's note: Jeremy makes an important distiction here that I completely agree with. I also must say that I absolutely hated that scene in Dragon Warrior. It ruined the end of that game for me. -Jay

The latest entry in our monthly RPG column recently espoused the mechanics of Alpha Protocol for providing the player with meaningful choice. But choice by itself does not create a unique experience. After all, the infamous “But thou must!” scene in the original Dragon Warrior technically gave you a choice: pick the correct response or stay in an infinite loop. However, the consequences behind those choices truly matter, not the choices themselves.

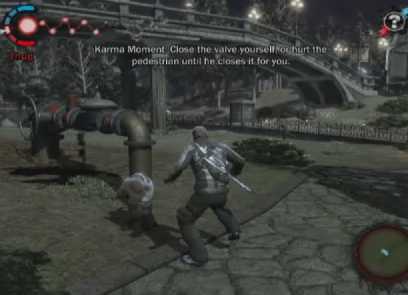

Many modern designers fall into the trap of choice for the sake of choice; they try to make the game meaningful with something that doesn’t change the experience much. Infamous exemplifies this in a particularly egregious way with the morality system the developers tacked on to the open-world gameplay. Its extremely binary nature nearly parodies other morality systems, but it really fails with its lack of consequences behind its choices.

Many modern designers fall into the trap of choice for the sake of choice; they try to make the game meaningful with something that doesn’t change the experience much. Infamous exemplifies this in a particularly egregious way with the morality system the developers tacked on to the open-world gameplay. Its extremely binary nature nearly parodies other morality systems, but it really fails with its lack of consequences behind its choices.

Occasionally, you’ll come across an event where you’ll be forced to choose between good and evil. Players will have no confusion about which is which, as big blue and red icons show exactly what they are. Your morality gauge will merely slide towards one side or the other. The only effects you'll encounter are abilities and endings exclusive to each alignment. The player does not encounter any meaningful consequences, as making either choice has no bearing on what happens next in the gameplay most of the time. Choosing one or the other becomes merely a constant questioning of whether the player wants to play as good or evil. While most games with a binary morality system provide more consequences than Infamous, the end result is often the same. Causes vastly outweigh the effects.

We shouldn't excuse this imbalance as a new concept, either. Landmark games like the Fallout series and Deus Ex pioneered consequence design years ago. Both provided many options for the player and connected choices with divergent gameplay to create vastly different experiences. The Fallout series, in particular, is famous for its ability to be completed in ten minutes depending on certain choices. Even the character development underpinnings had a tangible effect.

An extremely low intelligence score in both the original Fallout and Fallout 2 will limit your character's dialogue options to an extreme degree and render most choices into gibberish. I would not recommend playing Fallout like this, but the fact that this option even exists shows the game’s commitment to consequences. Deus Ex also provides this same sensation with different paths that depend on your approach. Variables like how characters treat you and even which bosses you fight can really create an experience that puts the player in control.

Some contemporary games understand how to properly implement consequences in new ways. Mass Effect 2 actually remembers your actions in the first game and builds your reputation around that. Little callbacks to missions you did before come back in unexpected places, from small exchanges with familiar faces to the trajectory of entire story missions. For instance, Wrex’s fate in the first game determines how warm a welcome you receive when you land on Tuchanka. Many of these instances don’t always bring gameplay benefits. However, they effectively draw the player into the world and Commander Shepard’s effect on it. Mass Effect 2’s infamous suicide mission, where your actions in the climax determines who survives, will undoubtedly bring heavier consequences into Mass Effect 3.

Some contemporary games understand how to properly implement consequences in new ways. Mass Effect 2 actually remembers your actions in the first game and builds your reputation around that. Little callbacks to missions you did before come back in unexpected places, from small exchanges with familiar faces to the trajectory of entire story missions. For instance, Wrex’s fate in the first game determines how warm a welcome you receive when you land on Tuchanka. Many of these instances don’t always bring gameplay benefits. However, they effectively draw the player into the world and Commander Shepard’s effect on it. Mass Effect 2’s infamous suicide mission, where your actions in the climax determines who survives, will undoubtedly bring heavier consequences into Mass Effect 3.

The recently released Alpha Protocol goes even further, packing countless choices and results into the game and interspersing them throughout. Every character has a relationship scale based on how much they like you. However, a person liking you is not always the ideal situation. Sometimes you have to make someone angry in order for them to divulge information. In addition, your handler trusts you more if they like you, but sometimes having them like you too much can negatively affect the mission. Gathering intel opens up conversation options. The order that you complete missions in changes what happens in future missions. You can't really supply a wrong answer, but the player’s approach and the results can vary wildly. But, in the end, meaningful choices make a game special, not just choices alone.

Player agency forms the core of games. Many games only limit this influence to player skill within a linear experience, but the potential for more is undeniable. As choice becomes more and more in vogue, developers would benefit from learning some fundamentals from the past. They need to make sure choices have tangible effects and don't create any logical gaps, reflect these consequences in the gameplay somehow, and, most importantly, make the players feel like their choices matter.