Editor’s note: Omar traces the evolution of non-linear storytelling and open world videogames, from Bubble Bobble and Zelda in the 1980s to this fall’s Dragon Age: Origins. Add your comments and contribute to the upcoming part two. -Demian

Many of us remember the "Choose Your Own Adventure" series with nostalgic affection. Each story was written using the second-person pronoun, allowing the reader to become the protagonist, making decisions which would affect the outcome and direction of the story. The series’ international popularity can be attributed to the sense of jurisdiction and responsibility given to readers who normally — being children — were rarely allowed to feel "in control."

For many of us, this was the first non-linear

story we had ever experienced.

Many famous films and books were published or released with alternate endings, and yet, before Ayn Rand’s Night of January 16th, very few authors or directors had attempted to employ multiple, independently-valid conclusions to a story. Those who did were met by very lukewarm, unenthusiastic responses from audiences and critics who were used to the didactic, instructive nature of Edwardian-era theatre and literature. The interactive nature of the "Choose Your Own Adventure" game-books popularized the notion of non-linearity throughout the late 70s and early 80s.

It Starts With a Quarter

It was in this period of creative experimentation of the early-1980s that several game developers began to embrace and explore the notion of non-linearity. The unique interaction between game designer and game player led Fukio Mitsuji of Taito to design and release Bubble Bobble, an arcade machine, in early 1986. Bubble Bobble, a co-operative game, presented different conclusions to the player depending on whether the second player was still alive and whether the players had completed the bonus levels. This divergence of narrative was contingent on the player’s actions, and as a result made Bubble Bobble the first game to introduce multiple, independent endings to a videogame.

With the unimaginable success of Taito’s arcade game, multiple endings quickly became commonplace. The replayability associated with multiple endings encouraged gamers to throw more quarters at the machines in order to witness all the possible conclusions. Soon enough, games like Bubble Bobble were producing more per-day/per-machine revenue than their more linear counterparts, which normally relied on the challenge of difficulty to entice gamers to play again.

Branching Storylines and Non-Linear Narrative

While the commercial success of non-linearity was quickly exploited, it wasn’t until its implementation on home console machines that developers began to contemplate the creative implications. The year after Bubble Bobble‘s release, the Nintendo R&D1 team, under Gunpei Yokoi, completed production of Metroid. The game was an immediate success, selling more than 500,000 copies in North America in its first year alone. Metroid offered five different endings to the player, depending on how quickly the player completed the game. The third, fourth, and fifth endings exposed the game’s hyper-masculine, alien-killing, screw attack-using protagonist to be a pretty blonde girl in a big red suit.

The vast majority of gamers didn’t see

this image during their first playthrough.

This profound shock inspired a wealth of contemporaneous and future videogame developers. The coming years and decades would introduce the notion of "choice" as an indispensable resource in story-telling in videogames. Gamers would go on to choose which final boss they would face in Chrono Trigger, whether or not they would accept the G-man’s Hobson-esque proposal, and which side of the Force they would follow. These, however, are games which only allow choices to be made at critical junctures. And while this was a step in the right direction, choosing whether or not kill Rosh Penin in Jedi Academy is simply a binary decision. What if the player wasn’t satisfied with the two options of reconciling with Rosh or brutally taking his life? Things in reality aren’t that two-dimensional, and so games still had a long way to go to truly achieve non-linearity.

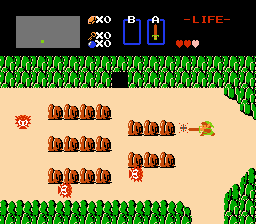

Games in every genre would eventually offer a choice of conclusion to the player, but for the Legend of Zelda series, multiple endings weren’t necessarily the solution to the question of creating narrative freedom. Zelda’s designers opted to supplement (or replace) the choice of narrative with a choice of physical direction. "Sandbox," "open world," and "emergent" design would all come to describe this loosely-defined concept. But the idea was the same: The player exists in a world and can interact with the world’s forces at his or her pace, and in a sequence of his or her choosing. Short of using that definition, the thinking applied to environment design in games like The Legend of Zelda and the original Shadowrun is best understood by the term…

The "sandbox" genre in its earliest form.

…Non-Linear Level Design

The original Legend of Zelda was released in Japan on February 21st, 1986, six months before Metroid and mere days after Bubble Bobble’s initial arcade announcement. Among the gauntlet of milestones which the game crossed, the Legend of Zelda was the first game to truly experiment with the notion of an open world. While Link was propelled down a relatively linear story, the player had the freedom to travel, explore, and do battle anywhere and anytime he or she pleased. The Legend of Zelda did away with the cattle corral style of storytelling, and instead employed a free range alternative, essentially pioneering the "sandbox" style of level design. While it may not look like it, behind all that car-jacking, wall-scaling, and impromptu demolition, companies like Take-Two (Grand Theft Auto), Ubisoft (Assassin’s Creed) and Volition (Red Faction: Guerrilla) took a page out of the Nintendo Handbook. I don’t mean to credit Nintendo with every achievement in storytelling, however it is difficult to deny their influence.

Drawing a line between this Link bravely wielding the Sword of Hyrule

and Altair shoving a blade into someone’s kidneys shouldn’t be too hard.

Joining Forces Between Direction and Narrative

In the years following, the flexible and player-dependent narrative of games like Metroid blended with the open world aspect of games like The Legend of Zelda. Surprisingly, the first game to truly brave that leap in history was not developed by Nintendo!

While games like 1994’s System Shock would perfect the compelling and immersive nature of a truly "open world," and 1996’s Baldur’s Gate would make quick work of a flexible, tailor-made narrative for each player, it wasn’t until Bethesda and Black Isle appeared that videogame stories and worlds began to look a little more convincing.

On August 30th, 1996, The Elder Scrolls: Daggerfall plunged a deep, poison-tipped dirk into the jugulars of gamers around the world. Allowing freeform play in a massive game world, Daggerfall was well-received for its bold venture into untested waters by every outlet which reviewed the game. However, it also suffered from debilitating bugs and defects, which made the appreciation of the game more difficult.

Fallout, System Shock and Elder Scrolls. If you’re not familiar with

these franchises, stop reading this and go out and buy them!

The following year, on September 30th, 1997, Fallout hit store shelves with the intention of perfecting the formula. Black Isle approached development with a very daunting philosophy. The team, led by Tim Cain and Leonard Boyarsky, wanted to create a game which would accommodate every individual, changing and reacting to the nature of the players, the choices they made and the experiences they were looking for. By all accounts and measurements, Black Isle accomplished that goal, with Fallout going on to receive the most flattering accolades from the likes of IGN, Gamespot and EGM. (Although it never got a platinum award, which I still believe is a travesty! Shoe, you’ve got some answering to do!)

In rapid succession, suddenly it wasn’t just RPGs which implemented adaptable, non-linear storylines, but all types of games. For the first time, the industry witnessed the possibility of roaming through foreign atmospheres and following compliant storylines from the first-person and third-person perspectives. Games like Fable and Oblivion would set examples as to how linearity could be shunned in favor of "freeform" and "emergent" gameplay.

This October, an important step will be taken in the direction of narrative and directional freedom. In games such as Fallout 3 and Prototype, each and every player begins from the exact same point of origin. And by now, you might get what I’m hinting at.

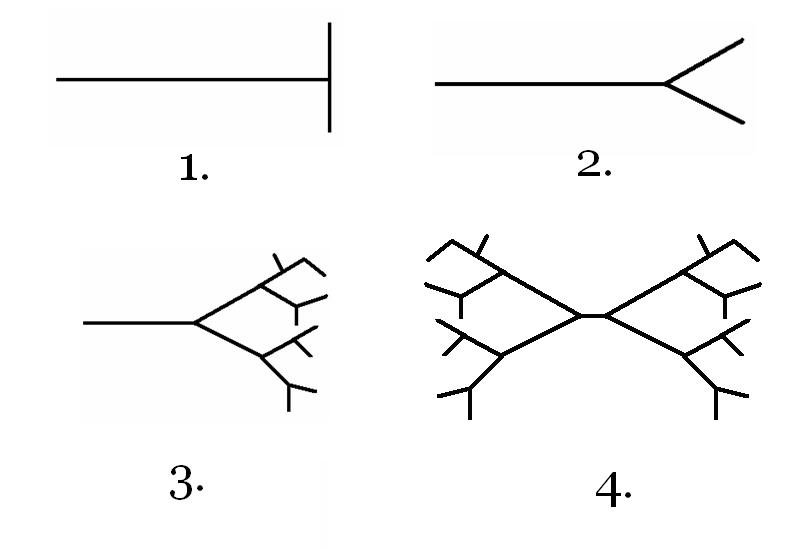

1. Bubble Bobble merely diverged at the very conclusion of the game.

2. Jedi Knight: Jedi Academy allowed the player to select one of two choices which dictated how the game ended.

3. The Elder Scrolls and Fallout series accommodated branching storylines, wherein almost every decision the player made propelled him or her down a different narrative path.

4. Dragon Age: Origins will allow players to begin their stories at different points of origin, with different motivations and different mentalities. If anything, this is a step in the right direction.

The problem here is one of origin. While players have come to choose the direction they move in and what sort of characters they wish to become, each and every gamer begins at the same start point. We all know that’s not how our real-life, personal stories have unfolded. I was born in Ottawa, Canada and my brother was born in Geneva, Switzerland. We will inevitably become different people. While our place of birth may be arbitrary, it certainly shapes who we are and who we will become. Being an enormous BioWare fan, I feel compelled to highlight the step which the company is taking towards true non-linearity in gaming.

Today, as gamers, we have the rare opportunity of imagining, without reservation, videogames which will offer us truly limitless choices in how we would like to direct our story experience. Games today allow us to choose which stories we want to be a part of, which part we want to play in that story and how big that part will be. We can choose to be heroes, villains, or innocent by-standers — all in the same continuity!

Now that we’ve gotten the history lesson out of the way, I’ll be back in a few days with a true analysis of non-linearity in videogames. In the meantime, I’d like to pose important questions to you, myself, and the community at large. What does the future hold for non-linear games? Can games like Fallout and Fable truly be considered non-linear, or is the player simply selecting one out of a limited number of stories? Will we ever be able to achieve absolute freedom in a videogame?

Hopefully, we’ll be able to tackle important notions within the nature of non-linear games. The "infinite ceiling of production costs," irreversibility, and morale/ethical decision making are all ideas which we should touch upon.

If you’ve got the time, place some responses in the comments section below. I’ll hopefully be able to include your opinions and thoughts in the second half of this two part investigative look at non-linearity.