Stealth-action video games fill out a genre that asks its players to surreptitiously navigate through an enemy-occupied area while maintaining discretion and avoiding detection. Popularized by Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear series — beginning in 1987 — they have seen the birth of many venerated franchises and been key participants in the mechanical cross-pollination of tropes throughout the rest of the medium. Of particular interest are the history, common heritage, and subsequent maturation of the genre, and how its development shapes not only stealth-centric games, but action and adventure titles going forward.

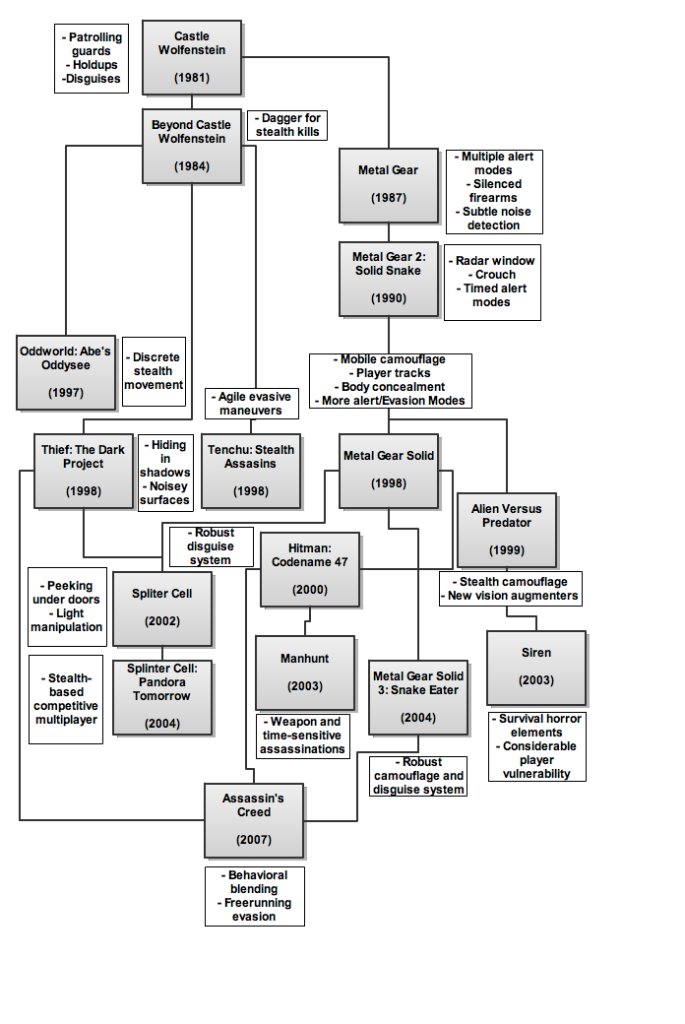

The genealogy of stealth games

The history tree (above) highlights efforts that either introduced or revised the conventions of the genre. Of course there are other games that incorporated components of stealth and evasion, but the games of chief interest, and those that I will now discuss, are the ones that introduced, expanded, and even standardized certain mechanics of covert action in stealth games. These are the salient games of the stealth genre, which represent significant milestones in the genus’ timeline.

The lineage of stealth-based video games goes back a long way. The act of eluding a predatory aggressor and evading them if noticed is the "flight" component in humanity's fight-or-flight response. It's a vital behavioral mechanism of survival that predates mankind. Avoiding conflict and violent confrontation is such an engrained part of the human condition that even children display a keen recognition of it. Thus, it is only natural that stealth appeared on the scene so early on in the history of video games.

One of modern stealth game's common ancestors is Castle Wolfenstein (Muse Software, 1981), originally released for the Apple II computer. In the game, participants must progress through a series of rudimentary corridors with the aim of reaching end zones and collecting secret war documents. Standing in the way of these exits are patrolling guards. The game arms the player with a gun, but ammo is scarce. Stronger enemy types take a considerably more ammunition to kill, which subsequently makes it increasingly difficult to win a gunfight. Dead guards leave behind ammo, keys, and bullet-proof vests.

Searching a body.

The firsts on Castle Wolfenstein’s feature list:

- Disguises: The player can find SS uniforms to wear. These will fool the base guard type, but not higher-ranking officers.

- A.I. alarm triggers: Sounds the player makes can alert the guards. They will only react to the sounds of gunfire, grenades, or the absence of a blending uniform. Once they the detect the player, they rush to confront the player.

- Holdups: If the player draws a firearm before a guard does, they can frisk the guard for resources.

Castle Wolfenstein serves as a model of convention for the stealth genre with many features that other games came to adopt. Among these descendants is Metal Gear (Konami, 1987), a prototypical work which began an illustrious franchise that was instrumental in stealth games coming to prominence.

Series architect Hideo Kojima created and designed Metal Gear. It incorporated core elements from Castle Wolfenstein, including alert patrol guards (with a straight line of sight to detect players) and the option to shoot enemies. It also added new features and included a more technically refined presentation. The feature set included the following:

- Overhead view

-

Multiple alert modes:

1) Only enemies in the player-occupied screen will attack.

2) Enemies descend on player from other screens. - Subtle noise detection: Guards become suspicious of close-range player movement and unsilenced gunfire.

- Silenced firearms: For long range stealth kills

- Cameras and infrared sensors: Obstacles that can spot players and alert guards.

- Melee attacks: Close-range stealth kills.

- Varied weapon arsenal: Including heavy weapons like a rocket launcher.

- Boss fights

- Hostage rescue

- Radio transceiver: A device that allows the player to correspond with ally characters.

- Safe screens: Areas of the level where pursuing guards do not follow.

The game's release didn’t send shockwaves through the industry or garner enough of a sparkling reception to put stealth games on the map, but it was successful enough to warrant a sequel. Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake (Konami, 1990) maintained the design framework of its forebearer while also introducing some noteworthy additions:

- Radar window: Highlights enemy locations and outlines level geometry.

- Continuous screens: Levels where seamless movement between areas is not confined to one screen.

- 45-degree field of vision: Guards have better sight.

- The ability to crouch: Provides a tactical advantage to hide in new hiding spots and reduces movement noise.

- Timed alert and evasion system: If the enemy spots the player, a countdown timer appears on screen. For the timer to reach zero, the guards cannt notice the hero again for the duration of the countdown. Once the timer reaches zero, the guards return to their normal patrol.

- Distraction items: These include robotic mice that lure guards to a desired location.

Going prone to avoid detection. New radar in the top right corner.

It wasn’t until 1998 that stealth-based games captured the attention and esteem of a very broad audience. Most notably, Metal Gear Solid (Konami, 1998), Kojima’s third stealth action game, became a seminal work that propelled the genre forward and proved a critical and commercial success — a feat its antecedents did not accomplish on this scale. It features polygonal graphics — thanks to the Sony PlayStation — and the game’s level design took advantage of this new dimension to create high and low areas, 360-degree player vision, and terrain topology. All of these made the player more vulnerable while also encouraging more recourse for stealth.

The player remains still next to a suspicious guard.

Metal Gear Solid built on the backbone of its forerunners by introducing new features for the franchise, which also became influential mainstays for stealth games and other genres:

- Mobile camouflage: The player can equip a cardboard box to conceal themselves while they negotiate an area.

- Player tracks: When the player walks through snow or picks up water on their shoes, they leave a trail of footprints behind. These tracks will arouse the suspicion of any guard who finds them, and they will then follow them to see where they lead.

- Body concealment: If the player incapacitates or kills any hostile guards, their bodies will remain, and the player must move them out of sight so another guard cannot find them and trigger an alert mode.

- Alert modes and enemy cooldowns: Not only is there an alert mode, but also an evasion mode, which follows. Evasion mode is another countdown until guards resume normal patrols, but their investigation of the player is more relaxed.

- Field of vision cones: A new vision scheme represented visually on the radar.

- Infra-red goggles

The game also added more context-sensitive disguises, distinct objectives that present unique challenges, and a greater emphasis on action and narrative. While one could argue that Metal Gear Solid almost single-handedly turned the tide for stealth games, some credit is due to Tenchu: Stealth Assassin (Activision, 1998) and Thief: The Dark Project (Looking Glass Studios, 1998) for stimulating a strong response to stealth action during the same year. Set in feudal Japan, Tenchu has the honor of being the first stealth video game from a 3D perspective. Its gameplay is characterized by agile, acrobatic evasive maneuvers, diverse stealth kills, and a reliance on melee weapons.

Thief is also set in antiquity, yet it's quite different. Unlike all of the games previously mentioned, the player has a first-person point of view. The game contains lock picking, detailed vocal remarks from enemies (this serves as the measure for how suspicious they are), and combat predicated on swordfighting. Thief made some very considerable contributions to stealth gameplay, which include acoustic floor surfaces (such as carpet or tile, which dampen noise made by walking or amplify it respectively) and shadow concealment (players are less visible when enshrouded in darkness, which is represented by a light/dark meter).

The player hides in shadows.

Convergence vs. evasion

All of the aforementioned games contain mechanics that greatly informed how developers would design stealth games in the future. These are the building blocks. They are the governing elements from which designers make all stealth scenarios in video games are made. In the past, a game like Thief might include a signature shadow concealment mechanic while Metal Gear Solid might now, or vice versa.

Today, however, stealth games are incorporating all of these distinct ingredients with the aim of developing more engaging games. No game better exemplifies this mechanical convergence than Splinter Cell (Ubisoft, 2002), a title that includes patrolling guards, A.I. distraction, alarms and alert modes, stealth kills, varied and contextual evasive maneuvers, shadow concealment, lethal and non-lethal tactics, hiding spots, and noise feedback.

At the same time, stealth mechanics have also infiltrated other game genres such as Siren (survival horror), S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl (first-person shooter), Fallout 3 (first-person role-playing game), The Chronicles of Riddick series (first-person shooter), and the Uncharted games (third-person action adventure). These titles all contain sequences or even core mechanics that share an outward resemblance to stealth games.

In more recent history, established franchises have been stressing action more than stealth. Designers have transplanted stealth-action protagonists into warzones (including Metal Gear Solid 4 and Splinter Cell: Double Agent) instead of isolated, enemy-occupied installations. Lethal firearm arsenals have increased — even to the point where roaming caravans of arms dealers offer a huge array of powerful weapons in a virtual war economy. Ammo, once traditionally scarce, has become more and more plentiful in the recent Metal Gear and Splinter Cell games. In addition, Splinter Cell: Conviction features a significantly faster, more agile protagonist who can easily mark and execute targets. Scripted sequences where confrontation is the only option have also appeared to increase in games like The Chronicles of Riddick: Assault On Dark Athena, Metal Gear Solid 3 and 4, and Splinter Cell: Double Agent.

I can only specuate as to why this trend has emerged. The stealth game has found its home mostly on console platforms like the PlayStation and Xbox. These platforms prominently promote many hardcore shooters and action games, which are flagship titles (Halo, Gears of War, Call of Duty, etc.) that have gained huge fanbases and reaped enormous revenue. This reflects a majority interest in user taste that favors games built on confrontation as the dominant play style.

Stealth games, on the other hand, are much less accommodating to players who seek frequent violent conflict. Instead, they appeal to players willing to hide, find egress, wait for enemy cooldowns, cope with limited resources, and adopt a relatively more passive approach to dealing with enemies. But the strengths of the genre rests in its accommodation of lethal and non-lethal tactics and its ability to create a different, more chilling brand of suspense.

Hopefully this trigger-happy trend will not go on to dominate stealth games. Instead, the opposite should occur — the stealth genre should continue to infuence action games, while also maintaining its own trademarks. Stealth fans should encourage developers to create solid, unique, and fiercely traditional ideas about how to approach the idea of conflict.

Works Cited

Cisarano, Jason. “The Unseen History of the Stealth Game”. Gaming Target, April 11, 2007. (Accessed February 20th, 2010).

http://www.gamingtarget.com/article.php?artid=6786&gameid=2481

Patterson, Shane. “The Sneaky History of Stealth Games”. Games Radar, February 3, 2009. (Accessed February 20th, 2010).

http://www.gamesradar.com/f/the-sneaky-history-of-stealth-games/a-2009020393535662028/p-5

Sallee, Mark Ryan. “Kojima’s Legacy”. IGN UK, June 9, 2006. (Accessed February 20th, 2010).

http://uk.ps2.ign.com/articles/715/715932p1.html

Shoemaker, Brad. “The History of Metal Gear”. Gamespot. (Accessed February 19th, 2010).

http://www.gamespot.com/gamespot/features/video/mg_history/index.html

Stallsworth, Eric. “The Top Five PC Stealth Games”. Bright Hub, May 28, 2009. (Accessed February 20th, 2010).