Pollen Music Group has done sound design and composed the music for over two dozen virtual reality films now, including Glen Keane’s Duet and Patrick Osborne’s Pearl, which is the first VR film to be nominated for an Academy Award. Most recently, it created Sonaria, a VR experience for the Google Spotlight Stories platform. Partnering with Chromosphere, it’s the first time Pollen has both directed the visuals as well as the sound. It’s available now on iOS and Android through the Google Spotlight Stories app, as well as on HTC Vive and the Oculus Rift through Steam.

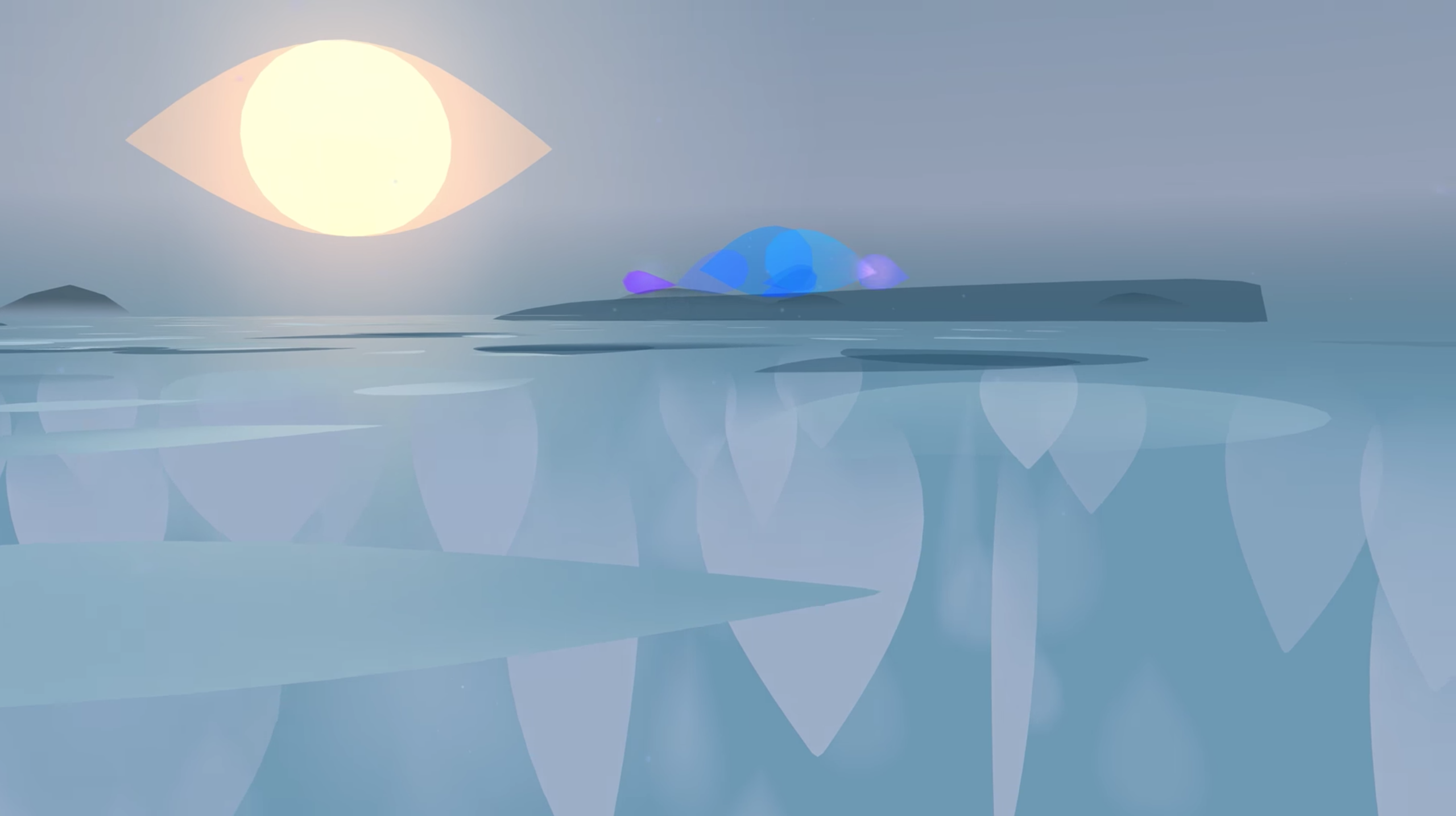

Sonaria follows the journey of two seals in a colorful world filled with geometric creatures. It has a pleasingly minimalist aesthetic, and it’s meant to be a relaxing experience that’s largely driven by the environment’s sounds.

Unlock premium content and VIP community perks with GB M A X!

Join now to enjoy our free and premium membership perks.

![]()

![]()