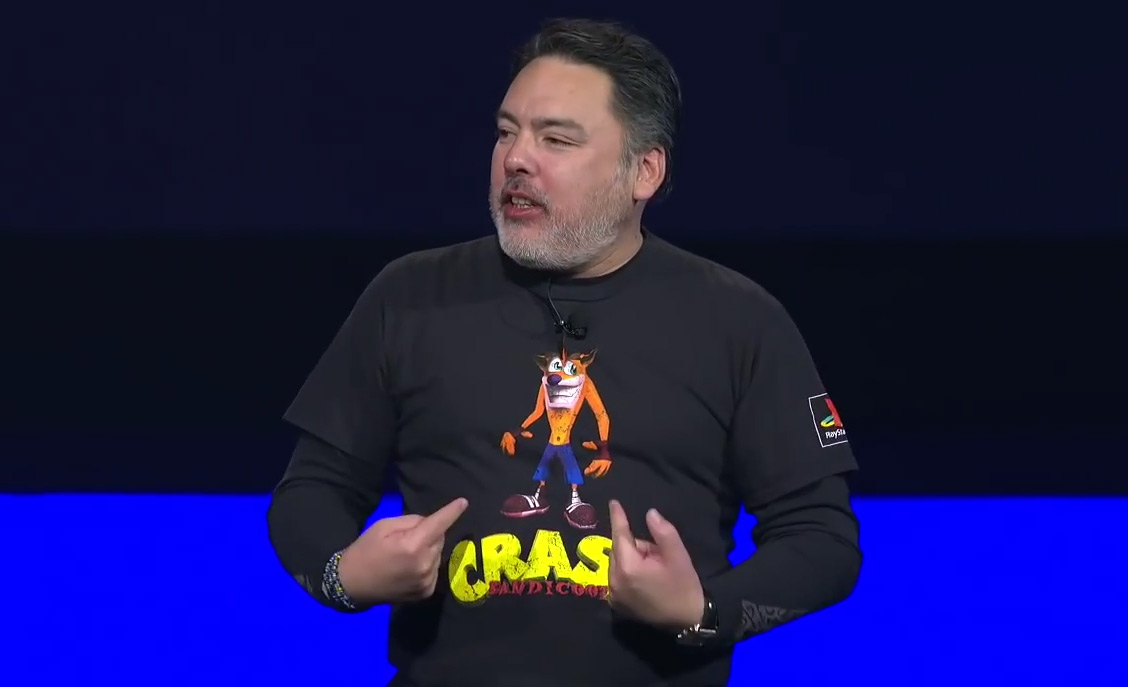

Shawn Layden was once so influential that his choice of a T-shirt determined the fate of a franchise. Back in 2015 during Sony’s PlayStation Experience event, Layden took the stage wearing a Crash Bandicoot shirt. Before thousands of fans, he talked about a long list of Sony games, but he didn’t say anything about a Crash Bandicoot game.

Fans were disappointed. Soon enough, Activision realized that there was pent-up demand for the little mascot, and it launched the Crash Bandicoot N. Sane Trilogy remake in 2017. It followed that up with another remake, Crash Team Racing: Nitro-Fueled, in 2019, and this week it unveiled Crash Bandicoot 4: It’s About Time. Millions of games were sold, all because of that T-shirt.

Unlock premium content and VIP community perks with GB M A X!

Join now to enjoy our free and premium membership perks.

![]()

![]()