Editor’s note: In the console wars, everyone’s a loser — I think Matthew’s preaching to the choir on that point. But it’s still interesting to read his experiences growing up in the DMZ between diehard Sega and Nintendo forces, as they battled for fanboy supremacy in British schoolyards. -Demian

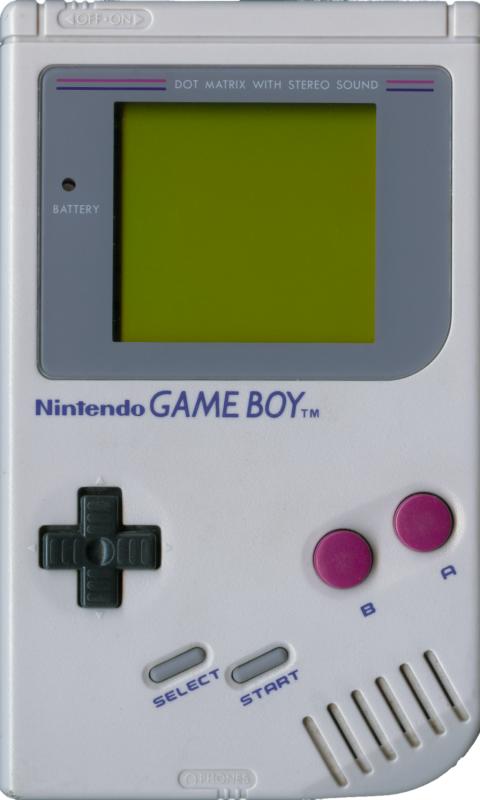

When I was about 12, I was negotiating to buy my friend Ben’s Nintendo Game Boy. There was a debate over money, which games would be included, whether he was going to throw in his set of accessories, but the final deal was to be decided upon at another friend’s birthday party.

Ben brought the goods with him and let me have a good go on the machine, way longer than the couple of minutes he’d usually allow. He sat beside me, the salesman in him telling me what I already knew: Tetris was amazing, Super Mario Land was great, Chase HQ was as good as it was in arcades (actually he was lying through his fucking teeth about that one). The pitch wasn’t necessary; I’d spent enough time pouring over articles and pictures of the Game Boy in magazines like Total! and Computer and Video Games to know that I wanted one, desperately….

Then into the party walked James with his Sega Game Gear, all color screen, sleek black casing, and Sonic the Hedgehog — a game designed to sway people like me from buying a Nintendo system. James was apparently done with it and was looking to sell. Decisions.

In the Britain of the 90s, unlike America, it was Sega’s Mega Drive that was overwhelmingly the most popular home console. I’d estimate that it was something like a 4:1 ratio of Sega to Nintendo fans at our school, and the division was stark. Sega’s aggressive marketing campaigns had paid off and made Nintendo seem old and for kids, while Sega seemed new and cool.

The break-time playground was filled with kids arguing, indeed fighting, over the relative merits of the two companies’ machines, and over the games they played. A line of associations was drawn in the sand and you were on one side or the other: Sonic or Mario; Road Rash or F-Zero; Mortal Kombat or Street Fighter.

The thing is, I never wanted to take part in those histrionics, thinking the attitude totally irrational. I can recall a group bike trip across town to a schoolmate’s house because we’d heard he’d got a copy of Desert Strike for his Mega Drive and we all wanted to see it. We did, and it was awesome. But just as awesome was the time another kid brought his SNES into school and we spent a lunch break playing Super Mario Kart.

There were people who refused to have a go on it, simply because it was a Nintendo game and they were Sega owners. But figuring it looked look like fun, I tried it, and you know what? Of course it was fun. I could never understand why anyone would outright dismiss a game based on which box of electronics it was programmed to play on. If you were a fan of computer games, why wouldn’t you want to play everything?

It’s possible that because of my gaming experience, I didn’t have much reason to feel invested in picking a side in a console war. Up to that point, I was almost totally a computer games player; d-pads and cartridges were alien to me. I was used to ZXOK controls, and loading games from tape and disk on the family Amstrad CPC 6128. (To the uninitiated, Z and X were typically used to move left and right, while O and K were up and down; SPACE was usually Fire or Jump. These were generally the default setting as most computers at the time didn’t have arrow keys!)

The Amstrad was a great computer, superior enough to notice a difference compared to its contemporaries, the ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64, but it was never leaps and bounds ahead. I had friends that had those computers, and since games were generally ported to all three, there wasn’t much jealousy between us. Sure, Fantasy Land Dizzy might have looked a bit better on one computer over the others, but we were still playing the same adventure.

Once the next wave of computers hit, things did change between me and those same friends. They both got Amiga 500s, while I got a PC. They quickly fell into the view that the PC was a work machine, suited only to making charts and writing letters in an office.

I was perfectly content with my PC and the games it had, but I still yearned for an Amiga. I loved the design; I loved the games; I loved the fact that when you slid a 3.5 inch disk into it, it ran any executable file off it without being asked; I loved the sounds it made. God I loved the sounds it made. But this desire was always in the context of addition, not substitution: I wanted an Amiga. And I wanted my PC. And I wanted my old Amstrad. And I wanted every console going. The thing stopping me was money, not allegiance. That my friends, who claimed to love computer games as much as me, didn’t share this view was as baffling then as it is today when I see people arguing over the PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and Wii.

[video:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQSsq7HCNHw 172×212]So when James walked into that party and showed me his Game Gear and asked if I was interested in it, there wasn’t any pretense when I said that I was. I spent some time with the system and enjoyed what I played. The color graphics were obviously superior to the Game Boy’s green monochrome, and the device actually felt more comfortable in my hands. I went back and forth all night, soliciting the opinions of my friends, getting the sort of decidedly unhelpful fanboy ‘arguments’ of which variations now infest video game messageboards across the Internet.

Eventually, I weighed up my options and decided on the Game Boy. The thing that swung it for me in the end wasn’t the peer pressure to own the ‘right’ system; it wasn’t a marketing campaign designed to make me feel cool. In the end it was down to something far more pragmatic: That Game Gear burned through a brand new set of six AAs during the course of the party. Like I said, back then it was about money, not allegiance. And actually, for me, it always will be.

Eventually, I weighed up my options and decided on the Game Boy. The thing that swung it for me in the end wasn’t the peer pressure to own the ‘right’ system; it wasn’t a marketing campaign designed to make me feel cool. In the end it was down to something far more pragmatic: That Game Gear burned through a brand new set of six AAs during the course of the party. Like I said, back then it was about money, not allegiance. And actually, for me, it always will be.