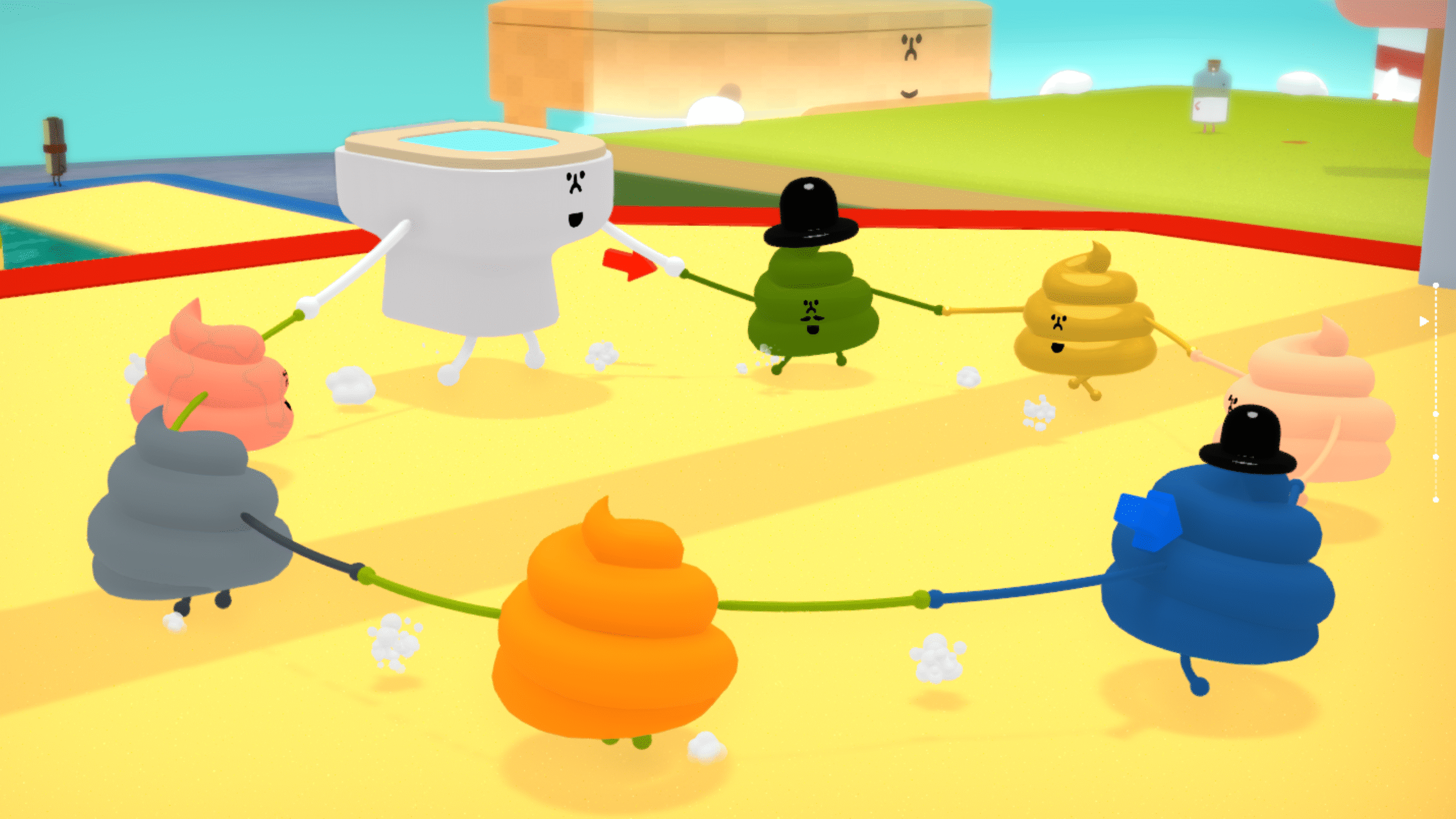

No one but Keita Takahashi could make a game like Wattam. He’s known for Katamari Damacy and Noby Noby Boy, and his newest project sports his signature cheery colors, goofy sense of humor, and playful mechanics. Even though it might appear as friendly chaos, it’s not all random — Takahashi created it with a reason in mind. He partnered with publisher Annapurna Interactive, and it will be due out later this year for PC and PlayStation 4.

Katamari Damacy came out in 2004, and its playful mechanics and zany, addictive soundtrack made it an instant classic. It won accolades, like the Excellence in Game Design award at the 2005 Game Developers Choice Awards, and it was later featured in the Museum of Modern Art as an example of the artistic merits of video games. Wattam doesn’t have the same mechanics, but like Katamari, it has an imaginative free spirit and radiates unrestrained joy.

Unlock premium content and VIP community perks with GB M A X!

Join now to enjoy our free and premium membership perks.

![]()

![]()